“What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.”

T.S. Elliot

We meet Brás de Oliva Domingos on his birthday. He’s sitting at a bar, wearing a tuxedo, on his way to celebrate the life of his father, who has recently passed away. There is blood on his tuxedo. He is 32.

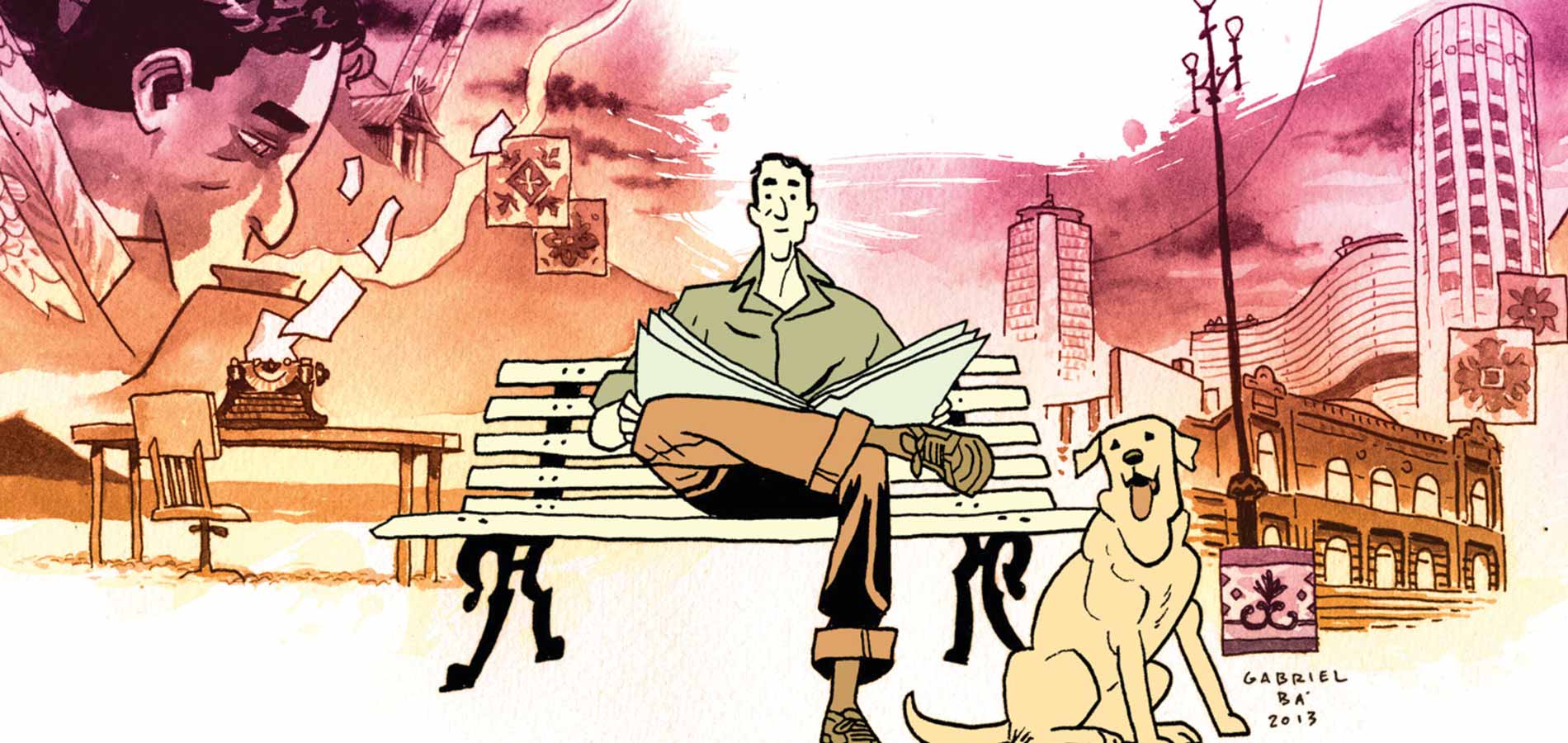

Death looms large in the life of Brás – a fact we are made privy to very early in the time we spend with him. He writes obituaries for a newspaper, describing lives through fondly sculpted memories. His work, though prolific in its own small way, is brimming with character. He describes the life of a famous painter, who had been in love with 274 different women in his life, proof of this being found in the portraits he would make of each lover, every painting carrying the name “Lola”. You know this painter for a fleeting moment, and yet a life has been spread before you, rife with nuance.

He is a master of words – a talent handed down to him from his father – though neither would openly admit this. Brás’ father was a famous writer and in his death, he was to be celebrated – though as cruel fate would have it, this celebration would occur on Brás’ own birthday. As he reads the paper detailing the soiree, he attempts to believe that his father would’ve balked at the suggestion of having the event occur as his son would begin another year of life. Reality says otherwise, however, and Brás is given a rough start to his 32nd birthday.

In short order, we see our hero struggling to stay above water, awash in a sea of memory. His typewriter was a gift from his father. A bad habit picked up from his mother bares his father’s fingerprints, the smoke coming from his favourite brand of cigarette. Throughout our inaugural trip with Brás, these themes of death, family and the attempt to live with and without both swirl until an ending. There is blood on his tuxedo. There is a gun in his face.

Brás dies on the date of his birth – and his story begins.

WHAT ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT DAYS OF YOUR LIFE?

Do you remember your first kiss? Your first love? Your one and only love? How about first loss? Your first personal failure? Your first death? In Daytripper, recounted in stunning clarity, we see the most important days of a man’s life. We see the lessons he learns from these moments, and the way his old life dies – only to be reborn anew inside of a new phase – an ending making way for a new beginning.

Each chapter is told without an effort made towards linear chronology – in its stead, events enfold in such a way that themes bleed from one story to the next – love, leading to loss, leading to love, leading to life, and over and over and over. Viewing a life in such a way is far and away out of the ordinary, but much more fulfilling and hearty. Each note hits at just the right frequency, resonating in your bones before ebbing and transforming into a fresh one, lyrics dancing beautifully atop the music you don’t so much as hear, but feel. The tune is familiar, but surprising in parts. You live alongside Brás. You die with him over and over and over. You heart aches and your heart breaks. You are haunted.

STORYTELLING

“I guess everyone that likes comics and likes to draw has this kind of notion that the drawings are the most important thing. And we were like that in the beginning. Now we care much more about the overall story. We don’t make too much effort to determine who is doing what, because in the end all that matter is the whole thing, the story we create and put out so people can read it. We don’t care who’s drawing. The artist doesn’t matter; the story is what matters.”

Fábio Moon from The Comics Journal No. 298, May 2009

The twins Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá are phenomenal storytellers – though most people only know them from working with writers such as Matt Fraction on Casanova and Gerard Way on The Umbrella Academy. And while their art styles are certainly very accomplished and evocative, their greatest strength lies in the way they tell a story. In their projects with other writers, this storytelling aspect is limited, in a sense, to what they can convey using other people’s words. In such cases, their art works as a bit of a mixtape, using the poetry of others and infusing it with your own deliberate choices, in order to make something different than what would’ve been through one voice alone. Inside the pages of Daytripper – as well as other works where they act both as writers and artists, the twins are left to tell stories with their own words.

In describing what they attempted to accomplish with this story in the back of its collected volume, Fábio Moon stated, “We wanted that feeling that life was happening right there, in front of every one of us, and we were living it. And we did. And sometimes, we die to prove that we lived.”

The words sum up the work as a whole more beautifully than I could ever hope to capture it – present in every page is a life well lived – one perfectly realized and captured using the drapes of small moments, dressing the bones of large, personal events. While adding their own measure of the fantastic to the regular events in a life, the twins manage to allow this story to become larger in the readers minds. Really, the story of Brás is no different than the story of mine or yours – but by adding the aspect of death, these everyday occurrences gain meaning. As Moon said, “We die to prove that we lived.” Death gives all moments meaning.

Without thinking about the story first, and letting the art really become a part of that, to be in service of that, rather than the driving force, this point is made with a subtle touch, staying at the fringes of your mind as you continue through one man’s life. And then, of course, there’s an ending – just as there must be with everything.

BEGINNING

There’s a magic present inside Daytripper that I can’t even hope to capture. I could go on for hours, for days attempting to parse every nuance, but the would be an exercise in fruitlessness. The book is much better experienced as it was always intended – through the medium of comics, wherein words can inform pictures, and pictures can carry words. It would do your heart good to go out and experience this book. Do it soon – because before long, something new will have to begin.

Brandon Schatz // Twitter // Facebook

You can support Submetropolitan by purchasing this book, and many more, at Variant Edition Comics + Culture – Canada’s best source for comics, used book + mindful pop culture.

Variant Edition // Website // Twitter // Facebook // Instagram